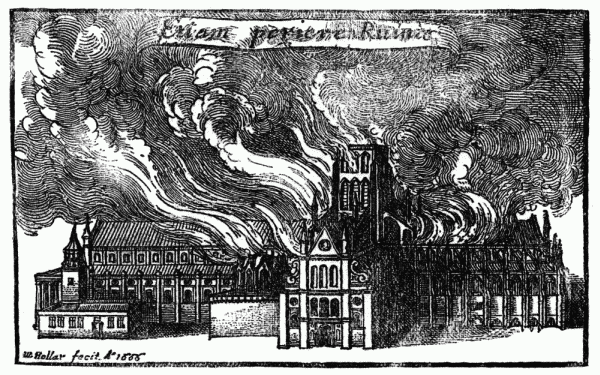

The Great Fire of London of 1666

London was still recovering from the Great Plague of 1665-6 when its residents became victims of another catastrophic tragedy: the Great Fire of London.

The fire, which took place in September 1666, began in Thomas Farriner’s bakery in Pudding Lane after a maid had closed the shop without putting out the ovens; as a result of the intense heat, sparks had flown and Farriner’s wooden home was set alight.

The fire began to spread rapidly and, once alerted, local constables and firemen sought to demolish the neighbouring buildings to precent further houses from being engulfed. However, the neighbours resisted and the Lord Mayor Sir Thomas Bloodworth was called in to settle the dispute.

Bloodworth refused to allow demolition of the houses, claiming that the fire was so minor “a woman could piss it out”. However, this decision was the turning point of this infamous event, which would soon completed engulf the wood-based city.

As the Great Fire of London started to spread across London people swarmed to green spaces, such as Hampstead Heath. It was at this point that Charles II (who had recently returned having fled the Plague of 1665 the year before) decided to take control of the blaze and gave permission for demolition.

Despite the king’s plans, the fire’s heat had become so intense that it had caused severe damage to some of the most notable buildings in London. In fact, the roof on St. Paul’s Cathedral actually melted away. Many pigeons died as a result of this, having refused to leave their nests, but the dramatic fire thankfully had little effect on the human population as many managed to flee their homes in time.

As Charles put his plans into place, authorities turned their attention to the River Thames. Many were fearful that the fire would somehow manage to cross the river and began spreading across south London, particularly as the winds seemed to be blowing it across the water. However, the weather turned in their favour and the wind began to flow in the opposite direction, driving the fire backwards across areas that were already destroyed and depriving it of flammable material. It was this that eventually resulted in the fire dying out.

Along with St. Paul’s Cathedral, a total of 84 churches were destroyed by the fire. However, it also demolished many areas affected by the Great Plague, and as a result there were no more large outbreaks of Plague after this date.

Once the fire was completely subdued, the authorities charged Sir Christopher Wren with rebuilding many of the most significant parts of the city, and much of his work still stands today.

"2 September: Jane (his maid) comes and tells us that she hears that above 300 houses have been burned down by the fire… poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats or clambering from one pair of stairs by the waterside, to another…I saw a fire as one entire arch of fire above a mile long: it made me weep to see it. The churches, houses are all on fire and flaming at once, and a horrid noise the flames made and the cracking of the houses."

MLA Citation/Reference

"The Great Fire of London of 1666". HistoryLearning.com. 2024. Web.