Second English Civil War

The English Civil War was divided into three seperate periods of fighting: the First English Civil War (1642-1646), the Second English Civil War (1648) and the Third English Civil War (1649-1651). The Second Civil English War took place between May and August 1648, featuring a number of battles that ultimately led to the defeat of Charles I and his subsequent execution in 1649.

On 11 November 1647, following the end of the First English Civil War, Charles I escaped from his imprisonment at Hampton Court. He travelled to the Isle of Wight, where he was re-imprisoned by Colonel Robert Hammond in Carisbrooke Castle. However, Charles was still able to begin negotiations with the Scots despite being captured. To ensure the support of the Scots, a deal was reached that stated that if the Scots invaded England and restored Charles to the throne, he would impose Presbyterianism in England for the following three years. By December 1647, negotiations between the king and Parliament had disintegrated and preparations were made for the Scots to invade England and make good on their promise.

At the same time, parliment was also suffering a decline in support across a number of strategically vital areas in England and Wales. For the most part, this was due to two key issues, including a lack of pay and concerns that the New Model Army was having too much of an influence on decision making within the government.

Once it had become widely known that Charles had secured an ally in the Scots, many people decided to transfer their allegiance. One person who did just this was Colonel Poyer, who was the governor of Pembroke Castle and one of the key parliamentary supporters during the First English Civil War.

Poyer had become disillusioned with the government, angered by the face that he was to be replaced and livid that he had not received his wages for many weeks. He was also particularly concerned about the fact that the New Model Army had increasing influence on the government and its decisions. Poyer’s anger was shared by others in South Wales, including Rowland Laugharne who had also been a key parliamentary supported during the First English Civil War.

As a result of his waining support, Oliver Cromwell was left with two options. The first was to ignore the dissent taking place in South Wales and elsewhere, particularly as South Wales itself could easily be cut off. The second, however, was to take action and so prevent further dissent from others considering swapping their allegiance.

Oliver Cromwell opted to take action, and in May 1648 he defeated Langharne and placed Pembroke Castle under siege.

Sadly for Cromwell, this upper hand was short lived and soon Kent decided to revolt against Parliament. Unlike South Wales, Kent was of great importance due to its proximity to London. The county also had a strong history of provided support to the royals, with the abolishment of Christmas resulting in serious riots in Canterbury on 25 December 1647.

In May 1648, the main leaders of these riots were arrested and put on trial but, much to the dismay of Anthony Weldon, Parliament’s representative in Kent, the charges were thrown out by the jury. Once the riot leaders were released they attempted to raise a petition that would attack the government’s county committee in Kent. Weldon attempted to prevent this with shear force and violence, but his attacks on provoked more anger among those already vexed; 10,000 people eventually came together near Rochester and declared the Earl of Norwich their new leader.

The responsibility of stopping the rebels was left to Thomas Fairfax, who met with the dissenters with the New Model Army at Blackheath. Fairfax won with ease, forcing the surrender of 1,000 rebels while many other simply fled. However, there were many towns in Kent, including Maidstone, that declared for the king.

Many of those who had fled the New Model Army joined other towns across the county, boosting numbers in key locations such as coastal forts. Around 3,000 even attempted to take London, although this quickly failed as the city gates were locked.

Among the rebels who sought to fight elsewhere were a large number who chose to flee to Essex. This boosted the number of Royalists in the county and the group soon felt they were strong enough to take Colchester. However, on 13 June 1648, Fairfax besieged the town in a vicious attack. More than 1,000 men were lost from the Parliamentarian force during the battle, but it wasn’t enough for the Royalists to take Colchester, particularly as aid from the Marquis of Hamilton and the Scots did not arrive as expected. By 27 August, Colchester surrendered to Fairfax.

While the Royalists were struggling in Essex, the Scots were beginning their journey down to England. In April 1648, a small force crossed the border and took Berwick, and just a few months later in July a larger force took Carlisle. By mid-July, 12,000 men made up the army of the Scots, all of them ready to march down to the south in support of Charles I.

Sadly, their advance was delayed, and this allowed enough time for a Parliamentarian force commanded by General John Lambert to cross the Pennines and attack the invading force. This was assisted by another troop of soldiers led by Oliver Cromwell, who had lost Pembroke Castle earlier in July. However, they found themselves confronted with Hamilton’s army, now numbering 20,000 men, which far outweighed the 9,000 (only 6,500 of which were skilled) of Cromwell.

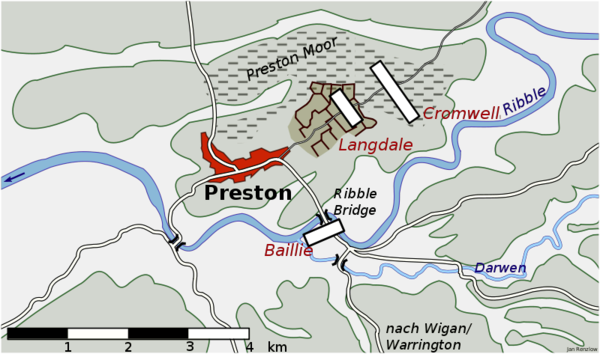

Cromwell still had the advantage of discipline, particularly as Hamilton’s army had spread across 20 miles - with the cavalry at the front and the infantry behind. On 17 August, he attached the infantry at the rear of Hamilton’s army in what became known as the Battle of Preston.

The fight took place in boggy terrain that made it incredibly difficult for the cavalry-heavy New Model Army. However, Cromwell used his horses to bludgeon the Scots and forced Hamilton to reign in his soldiers from far and wide in an attempt to regain control. As a result of the huge distances between his troops, Hamilton lost 4,000 soldiers to death and another 4,000 to capture on 17 August alone.

The night between the 17 and 18 August was incredibly wet, leaving many Scots soaked through and unable to use some of their ammunition. As a result, the battle on the following day was incredibly bloody and it wasn’t long before the men began to surrender. Those who were volunteers were treated cruelly, being sent to Barbados or Virginia as slaves, while those who were conscripted were sent home.

As a result of the mismanagement of Hamilton’s army, Charles had no Scottish support and lost his cause. His only remaining Royalist support was in Pontefract Castle, which held out until after his trial and execution but eventually surrendering in March 1649.

See also: The Battle of Preston

MLA Citation/Reference

"Second English Civil War". HistoryLearning.com. 2024. Web.